Why Arbitration Struggles to Take Root in Thailand: Unpacking the Challenges

Arbitration, often hailed as a faster, more flexible alternative to traditional litigation, has yet to win over the hearts and minds of Thailand’s commercial and legal communities. Despite its global reputation as an efficient dispute resolution mechanism, arbitration in Thailand remains overshadowed by the country’s court system. The reasons for this are complex, rooted in a mix of cultural, legal, and practical barriers that continue to stifle its growth. While there are glimmers of progress, significant challenges persist—here’s a closer look at why arbitration hasn’t quite found its footing in the Land of Smiles.

A Knowledge Gap That’s Hard to Bridge

One of the most glaring obstacles is a simple lack of awareness. Many businesses in Thailand—small and large alike—don’t fully understand what arbitration entails or how it could benefit them. For the average company, the court system feels like a known quantity: familiar, predictable, and deeply entrenched in the national psyche. Arbitration, by contrast, can seem abstract or even intimidating. Why opt for something untested when the courts have been the go-to for generations?

Efforts to change this are underway. Organizations like the Thailand Arbitration Center (THAC) under the Ministry of Justice and Thailand Arbitration Institute (TAI) under the Court of Justice and other bodies have launched campaigns to educate stakeholders about arbitration’s advantages—confidentiality, speed, and the ability to choose your decision-maker, to name a few. But these initiatives are still in their early stages, and their reach remains limited. Without a broader shift in understanding, arbitration risks staying on the sidelines, a niche option for the few rather than a mainstream tool for the many.

Cultural Ties to the Courts

Thailand’s preference for traditional dispute resolution runs deeper than just familiarity—it’s cultural. The judiciary holds a revered place in Thai society, seen as a pillar of stability and authority. Arbitration, on the other hand, carries a whiff of skepticism, especially after high-profile cases involving state entities that left a sour taste. When multimillion-dollar disputes with government agencies have ended in controversial arbitral rulings, the fallout has fueled a perception that arbitration might not be as trustworthy or impartial as the courts. This historical baggage weighs heavily, particularly in cases tied to public interest, where the stakes—and scrutiny—are sky-high.

This cultural lean isn’t just about habit; it’s about trust. For many Thai businesses and individuals, handing over a dispute to a private arbitrator feels like a leap of faith compared to the structured, state-backed process of litigation. Breaking that mindset will require more than education—it’ll take a cultural reframing of how disputes can and should be resolved.

Courts: Allies or Obstacles?

On paper, Thailand’s legal framework supports arbitration. The country is a signatory to the New York Convention, and recent court decisions suggest a more pro-arbitration stance. But in practice, judicial attitudes can still throw a wrench in the works. Thai courts have a history of setting aside arbitral awards on grounds like “public policy” or “morals”—terms vague enough to invite interpretation and inconsistent enough to erode confidence. When a hard-won arbitral award can be overturned for reasons that feel arbitrary, it’s no wonder parties think twice before committing to the process.

Then there’s the red tape for government agencies. Under Thai law, state entities need special approval to include arbitration clauses in contracts—a hurdle that doesn’t exactly scream “arbitration-friendly.” This restriction not only slows down adoption but also sends a signal that arbitration is secondary, a last resort rather than a first choice. Until the judiciary and government fully embrace arbitration as an equal partner to litigation, its credibility will remain on shaky ground.

The Arbitrator Shortage

Even if awareness and trust were in place, there’s a practical problem: Thailand lacks a deep bench of qualified arbitrators. International disputes, in particular, demand professionals with specialized expertise, fluency in languages like English or Chinese, and a firm grasp of complex procedural rules. While Thailand has skilled legal minds, the pool of arbitrators meeting these criteria is still small. For businesses weighing their options, the prospect of an inexperienced or underqualified arbitrator can be a dealbreaker—especially when they could instead turn to a seasoned judge in the court system.

This scarcity also limits Thailand’s appeal as a regional arbitration hub. Neighboring countries like Singapore and Hong Kong have built thriving arbitration ecosystems partly by cultivating a robust roster of experts. If Thailand wants to compete, it’ll need to invest in training and attracting top-tier arbitrators—a long-term project that’s only just beginning.

Enforcement Woes and Efficiency Doubts

Arbitration’s promise of speed and finality doesn’t always hold up in Thailand. Enforcing an arbitral award can turn into a slog, with losing parties deploying delay tactics to drag out proceedings. What starts as a streamlined alternative can end up mired in the same frustrations as litigation, chipping away at arbitration’s appeal. Add to that the absence of third-party funding—a mechanism that helps level the playing field in places like Singapore or the UK—and access becomes an issue. For smaller businesses or individuals, the upfront costs of arbitration can feel prohibitive without financial backing.

Efficiency isn’t just about time; it’s about certainty. When enforcement feels uncertain or unpredictable, the whole value proposition of arbitration starts to unravel. Why choose a process that might leave you fighting the same battle twice?

A Path Forward

Despite these hurdles, there’s reason for cautious optimism. The Thai government and arbitration advocates are pushing for reforms—streamlining enforcement, expanding arbitrator training, and promoting arbitration as a viable option for domestic and international disputes. Younger generations of lawyers and business leaders, exposed to global practices, may also help shift attitudes over time. If these efforts gain momentum, arbitration could slowly shed its underdog status.

For now, though, arbitration in Thailand remains a work in progress. It’s caught between a legal system that’s evolving and a society that’s hesitant to let go of tradition. Addressing the knowledge gap, building trust, and tackling practical barriers will be key to unlocking its potential. Until then, the courts will likely keep their crown as Thailand’s dispute resolution king—but arbitration’s day may still come.

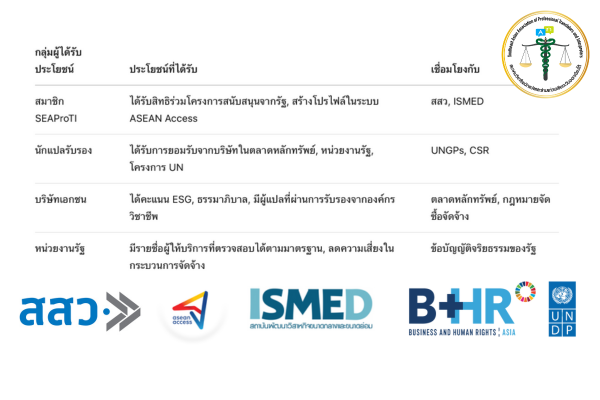

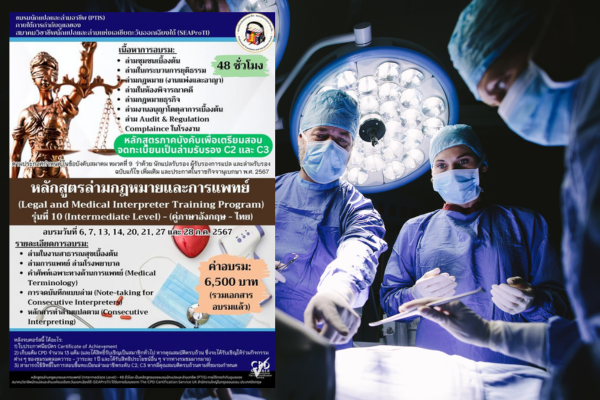

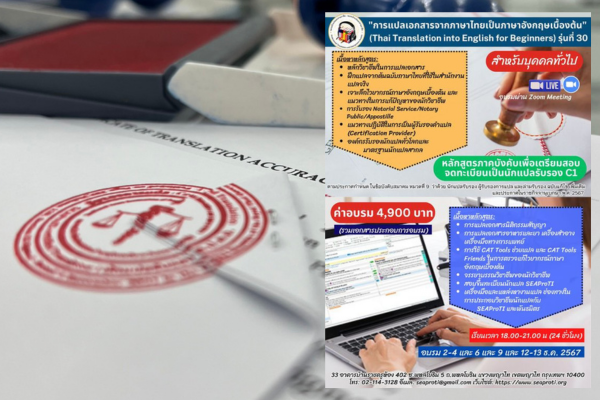

SEAProTI’s certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters:

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for individuals to register as “Certified Translators,” “Translation Certification Providers,” and “Certified Interpreters” under the association’s regulations. These guidelines are detailed in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet under the Office of the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, dated July 25, 2024, Volume 141, Part 66 Ng, Page 100.

To read the full publication, visit: the Royal Thai Government Gazette

ทำไมการอนุญาโตตุลาการยังไม่ได้รับความนิยมในประเทศไทย: เจาะลึกอุปสรรคต่าง ๆ

การอนุญาโตตุลาการ ซึ่งมักถูกยกย่องว่าเป็นทางเลือกที่รวดเร็วและยืดหยุ่นกว่าการฟ้องร้องแบบดั้งเดิม ยังไม่สามารถชนะใจชุมชนการค้าและกฎหมายในประเทศไทยได้ แม้จะมีชื่อเสียงระดับโลกว่าเป็นกลไกการระงับข้อพิพาทที่มีประสิทธิภาพ แต่ในประเทศไทย การอนุญาโตตุลาการยังคงถูกบดบังโดยระบบศาล สาเหตุของเรื่องนี้ซับซ้อน มาจากอุปสรรคทั้งด้านวัฒนธรรม กฎหมาย และการปฏิบัติที่ยังคงขัดขวางการเติบโตของมัน แม้จะมีสัญญาณของความก้าวหน้า แต่ปัญหาสำคัญ ๆ ยังคงมีอยู่—มาดูกันว่าเหตุใดการอนุญาโตตุลาการยังไม่สามารถหยั่งรากในดินแดนแห่งรอยยิ้มได้

ช่องว่างความรู้ที่ยากจะเติมเต็ม

หนึ่งในอุปสรรคที่เห็นได้ชัดเจนที่สุดคือการขาดความตระหนักรู้ ธุรกิจในประเทศไทยทั้งขนาดเล็กและใหญ่จำนวนมากยังไม่เข้าใจอย่างถ่องแท้ว่าการอนุญาโตตุลาการคืออะไร หรือมันจะเป็นประโยชน์ต่อพวกเขาอย่างไร สำหรับบริษัททั่วไป ระบบศาลดูเหมือนเป็นสิ่งที่คุ้นเคย: เข้าใจง่าย คาดเดาได้ และฝังรากลึกในจิตสำนึกของชาติ ในทางกลับกัน การอนุญาโตตุลาการอาจดูเป็นนามธรรมหรือน่ากลัวด้วยซ้ำ แล้วทำไมต้องเลือกสิ่งที่ไม่เคยลอง เมื่อศาลเป็นตัวเลือกที่ใช้กันมานานหลายชั่วอายุคน

มีความพยายามที่จะเปลี่ยนแปลงสิ่งนี้อยู่ องค์กรอย่าง สถาบันอนุญาโตตุลาการ (THAC) ของกระทรวงยุติธรรม และ สถาบันอนุญาโตตุลาการ (THAC) ของศาลยุติธรรม และหน่วยงานอื่น ๆ ได้เริ่มรณรงค์เพื่อให้ความรู้แก่ผู้มีส่วนได้ส่วนเสียเกี่ยวกับข้อดีของการอนุญาโตตุลาการ เช่น ความเป็นส่วนตัว ความรวดเร็ว และความสามารถในการเลือกผู้ตัดสิน แต่ความพยายามเหล่านี้ยังอยู่ในช่วงเริ่มต้น และการเข้าถึงยังจำกัด หากไม่มีการเปลี่ยนแปลงความเข้าใจในวงกว้าง การอนุญาโตตุลาการอาจยังคงอยู่นอกสายตา เป็นตัวเลือกเฉพาะกลุ่มแทนที่จะเป็นเครื่องมือหลักสำหรับคนส่วนใหญ่

ความผูกพันทางวัฒนธรรมกับศาล

ความนิยมในวิธีการระงับข้อพิพาทแบบดั้งเดิมของประเทศไทยไม่ได้มาจากแค่ความคุ้นเคย มันเป็นเรื่องของวัฒนธรรม ศาลยุติธรรมถือเป็นเสาหลักของความมั่นคงและอำนาจในสังคมไทย ในขณะที่การอนุญาโตตุลาการกลับมีความสงสัยตามมา โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งหลังจากคดีสำคัญที่เกี่ยวข้องกับหน่วยงานของรัฐที่ทิ้งความรู้สึกไม่ดีไว้ เมื่อข้อพิพาทมูลค่าหลายล้านบาทกับหน่วยงานรัฐสิ้นสุดลงด้วยคำตัดสินอนุญาโตตุลาการที่ขัดแย้งกัน ผลที่ตามมาได้จุดประกายความรู้สึกว่าการอนุญาโตตุลาการอาจไม่น่าเชื่อถือหรือเป็นกลางเท่าศาล ความเสียหายในอดีตนี้มีน้ำหนักมาก โดยเฉพาะในคดีที่เกี่ยวข้องกับผลประโยชน์สาธารณะ ซึ่งทั้งเดิมพันและการจับตามองสูงมาก

ความโน้มเอียงทางวัฒนธรรมนี้ไม่ใช่แค่เรื่องนิสัย แต่เป็นเรื่องความไว้วางใจ สำหรับธุรกิจและบุคคลชาวไทยจำนวนมาก การมอบข้อพิพาทให้กับอนุญาโตตุลาการส่วนตัวรู้สึกเหมือนเป็นการกระโดดลงไปในความไม่แน่นอน เมื่อเทียบกับกระบวนการที่มีโครงสร้างและได้รับการสนับสนุนจากรัฐอย่างการฟ้องร้อง การเปลี่ยนแปลงทัศนคตินี้จะต้องใช้มากกว่าการศึกษา มันต้องมีการปรับกรอบความคิดใหม่ทั้งหมดเกี่ยวกับวิธีการระงับข้อพิพาท

ศาล: เพื่อนหรืออุปสรรค

ในทางทฤษฎี กรอบกฎหมายของประเทศไทยสนับสนุนการอนุญาโตตุลาการ ประเทศไทยเป็นภาคีของอนุสัญญานิวยอร์ก และคำตัดสินของศาลล่าสุดบ่งบอกถึงท่าทีที่เป็นมิตรต่อการอนุญาโตตุลาการมากขึ้น แต่ในทางปฏิบัติ ทัศนคติของศาลยังสามารถสร้างปัญหาได้ ศาลไทยมีประวัติการยกเลิกคำชี้ขาดของอนุญาโตตุลาการด้วยเหตุผลอย่าง “นโยบายสาธารณะ” หรือ “ศีลธรรม” คำที่คลุมเครือพอที่จะเปิดช่องให้ตีความ และไม่สม่ำเสมอพอที่จะบั่นทอนความเชื่อมั่น เมื่อคำชี้ขาดที่ได้มาอย่างยากลำบากสามารถถูกยกเลิกด้วยเหตุผลที่ดูไม่ชัดเจน ใครจะกล้าเลือกกระบวนการนี้

แล้วยังมีขั้นตอนยุ่งยากสำหรับหน่วยงานรัฐ ตามกฎหมายไทย หน่วยงานของรัฐต้องได้รับอนุญาตพิเศษเพื่อใส่ข้อตกลงอนุญาโตตุลาการในสัญญา นี่คืออุปสรรคด้านขั้นตอนที่ไม่ได้ตะโกนว่า “เป็นมิตรต่อการอนุญาโตตุลาการ” แน่นอน ข้อจำกัดนี้ไม่เพียงแต่ชะลอการยอมรับ แต่ยังส่งสัญญาณว่าการอนุญาโตตุลาการเป็นตัวเลือกอันดับสอง เป็นทางออกสุดท้ายมากกว่าตัวเลือกแรก จนกว่าศาลและรัฐบาลจะยอมรับการอนุญาโตตุลาการอย่างเต็มที่ในฐานะหุ้นส่วนที่เท่าเทียมกับการฟ้องร้อง ความน่าเชื่อถือของมันจะยังคงไม่มั่นคง

ปัญหาการขาดแคลนอนุญาโตตุลาการ

ถึงแม้ความตระหนักรู้และความไว้วางใจจะพร้อม แต่ก็ยังมีปัญหาในทางปฏิบัติ: ประเทศไทยขาดแคลนอนุญาโตตุลาการที่มีคุณสมบัติเหมาะสม ข้อพิพาทระหว่างประเทศโดยเฉพาะ ต้องการผู้เชี่ยวชาญที่มีความรู้เฉพาะทาง ความคล่องแคล่วในภาษาอย่างอังกฤษหรือจีน และความเข้าใจในกฎระเบียบที่ซับซ้อน แม้ว่าประเทศไทยจะมีนักกฎหมายที่มีฝีมือ แต่กลุ่มอนุญาโตตุลาการที่ตรงตามเกณฑ์เหล่านี้ยังมีจำนวนน้อย สำหรับธุรกิจที่กำลังชั่งใจตัวเลือก การเผชิญกับอนุญาโตตุลาการที่ขาดประสบการณ์หรือคุณสมบัติอาจทำให้เปลี่ยนใจโดยเฉพาะเมื่อพวกเขาสามารถหันไปหาผู้พิพากษาที่มีประสบการณ์ในระบบศาลได้

ความขาดแคลนนี้ยังจำกัดความน่าสนใจของประเทศไทยในฐานะศูนย์กลางอนุญาโตตุลาการระดับภูมิภาค ประเทศเพื่อนบ้านอย่างสิงคโปร์และฮ่องกงได้สร้างระบบอนุญาโตตุลาการที่เจริญรุ่งเรือง ส่วนหนึ่งโดยการพัฒนากลุ่มผู้เชี่ยวชาญที่แข็งแกร่ง หากประเทศไทยต้องการแข่งขัน จะต้องลงทุนในการฝึกอบรมและดึงดูดอนุญาโตตุลาการชั้นนำซึ่งเป็นโครงการระยะยาวที่เพิ่งเริ่มต้น

ปัญหาการบังคับใช้และข้อสงสัยเรื่องประสิทธิภาพ

คำสัญญาของการอนุญาโตตุลาการเรื่องความรวดเร็วและความเด็ดขาดไม่ได้เป็นจริงเสมอไปในประเทศไทย การบังคับใช้คำชี้ขาดอาจกลายเป็นเรื่องยุ่งยาก โดยฝ่ายที่แพ้ใช้กลยุทธ์เพื่อยืดเวลา สิ่งที่เริ่มต้นจากการเป็นทางเลือกที่คล่องตัว อาจจบลงด้วยความยุ่งยากเหมือนการฟ้องร้อง ซึ่งทำลายความน่าสนใจของมันไป ยิ่งไปกว่านั้น การขาดตัวเลือกการระดมทุนจากบุคคลที่สาม กลไกที่ช่วยให้การแข่งขันเป็นธรรมในที่อย่างสิงคโปร์หรือสหราชอาณาจักร ทำให้การเข้าถึงเป็นปัญหา สำหรับธุรกิจขนาดเล็กหรือบุคคลทั่วไป ต้นทุนล่วงหน้าของการอนุญาโตตุลาการอาจรู้สึกหนักเกินไปหากไม่มีผู้สนับสนุนทางการเงิน

ประสิทธิภาพไม่ได้เกี่ยวกับเวลาเท่านั้น แต่ยังเกี่ยวกับความแน่นอน เมื่อการบังคับใช้รู้สึกไม่แน่นอนหรือคาดเดาไม่ได้ คุณค่าของการอนุญาโตตุลาการก็เริ่มคลายตัว แล้วทำไมต้อง

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง