When Thai Arbitrators Lack Neutrality:

Consequences of Assisting One Party in Preparing Witness Examination

22 February 2025, Bangkok – In Thailand, arbitration has emerged as a favored mechanism for resolving disputes outside traditional courts, valued for its efficiency, flexibility, and confidentiality. Governed by the Arbitration Act B.E. 2545 (2002), the success of this process hinges on a fundamental principle: the impartiality of the arbitrator. However, when a Thai arbitrator compromises this neutrality—for instance, by assisting one party’s lawyer in rehearsing witness examination to question the opposing side’s witnesses—the repercussions are profound, affecting legal integrity, ethical standards, and the credibility of Thailand’s arbitration system. This article explores these consequences in detail.

1. Undermining Fairness in the Process

Under Section 19 of the Arbitration Act B.E. 2545, Thai arbitrators are legally obligated to act independently and without bias. Assisting one party’s counsel in preparing witness examination—such as suggesting questions or strategies to undermine the opposing side’s witnesses—directly violates this duty. Such actions erode the fairness of the proceedings, leaving the disadvantaged party with a justified sense of injustice. This breach of impartiality jeopardizes the legitimacy of the entire arbitration process, potentially leading to the rejection of the arbitrator’s final award by the affected party.

2. Impact on the Arbitral Award

The Arbitration Act B.E. 2545, under Section 40, allows a party to petition a Thai court to set aside an arbitral award if the process was unjust or the arbitrator exhibited bias. Should the disadvantaged party uncover evidence of the arbitrator’s misconduct—such as records of conversations or witness testimony proving collusion with the opposing side—the court could nullify the award. This outcome renders the time, effort, and expense invested in arbitration futile, forcing the parties to either restart the process or resort to litigation. Such a scenario defeats the very purpose of choosing arbitration as an efficient dispute resolution method.

3. Ethical and Reputational Fallout

Arbitrators in Thailand are often respected professionals—former judges, seasoned lawyers, or academics—whose credibility underpins their appointments. Engaging in biased behavior, such as aiding one party in witness preparation, constitutes a serious breach of professional ethics. Beyond personal consequences, this misconduct tarnishes the reputation of affiliated institutions, such as the Thailand Arbitration Center (THAC). If exposed publicly, it could spark criticism and erode trust in Thailand’s arbitration framework, deterring both domestic and international parties—particularly investors—from relying on it.

4. Practical Implications for the Dispute

When an arbitrator assists one side in rehearsing witness examination, the advantaged party gains an unfair edge. For example, they might preemptively identify weaknesses in the opposing witnesses or craft questions designed to distort the facts. This imbalances the presentation of evidence, skewing the arbitration toward an outcome that may not reflect the full truth. The disadvantaged party, unaware of the collusion, is left vulnerable, and the resulting award risks being unjust.

5. Solutions and Preventive Measures

To safeguard against such issues, Thailand’s arbitration system must strengthen oversight and accountability. Clear guidelines prohibiting ex parte communication between arbitrators and parties, coupled with regular ethics training, could reinforce impartiality. Additionally, under Section 20 of the Arbitration Act, parties should feel empowered to challenge an arbitrator’s appointment at the earliest sign of bias. Transparent mechanisms for reporting and addressing misconduct would further bolster confidence in the system.

Conclusion

When a Thai arbitrator abandons neutrality by helping one party prepare witness examinations to question the other side’s witnesses, the consequences are far-reaching. The process loses its fairness, the arbitral award faces legal challenges, and the reputations of both the arbitrator and the broader system suffer. This not only undermines individual cases but also threatens Thailand’s standing as a reliable hub for dispute resolution. Upholding impartiality is not merely an arbitrator’s duty—it is the cornerstone that ensures arbitration remains a trusted alternative to litigation in Thailand.

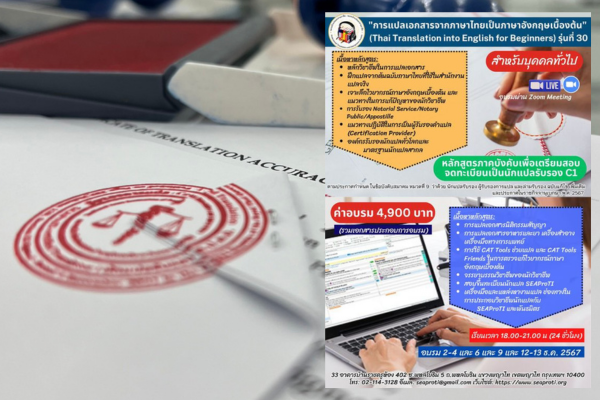

SEAProTI’s certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters:

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for individuals to register as “Certified Translators,” “Translation Certification Providers,” and “Certified Interpreters” under the association’s regulations. These guidelines are detailed in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet under the Office of the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, dated July 25, 2024, Volume 141, Part 66 Ng, Page 100.

To read the full publication, visit: the Royal Thai Government Gazette

เมื่ออนุญาโตตุลาการไทยไม่เป็นกลาง: ผลกระทบจากการช่วยซ้อมการซักถามพยาน

22 กุมภาพันธ์ 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ในระบบกฎหมายไทย อนุญาโตตุลาการ (Arbitration) ถือเป็นกลไกสำคัญในการระงับข้อพิพาทนอกศาลที่ได้รับความนิยมมากขึ้นเรื่อย ๆ เนื่องจากความรวดเร็ว ความยืดหยุ่น และความเป็นส่วนตัว อย่างไรก็ตาม ความสำเร็จของกระบวนการนี้ขึ้นอยู่กับหลักการสำคัญประการหนึ่ง นั่นคือ ความเป็นกลาง (Impartiality) ของอนุญาโตตุลาการ หากอนุญาโตตุลาการไทยไม่สามารถรักษาความเป็นกลางได้ เช่น กรณีที่อนุญาโตตุลาการช่วยทนายฝ่ายหนึ่งซ้อมการซักถามพยานเพื่อใช้ถามพยานของอีกฝ่าย จะเกิดผลกระทบร้ายแรงทั้งในแง่กฎหมาย จริยธรรม และความน่าเชื่อถือของระบบอนุญาโตตุลาการ ดังจะกล่าวต่อไปนี้

1. การบ่อนทำลายความเป็นธรรมในกระบวนการ

กระบวนการอนุญาโตตุลาการในประเทศไทยอยู่ภายใต้พระราชบัญญัติอนุญาโตตุลาการ พ.ศ. 2545 ซึ่งกำหนดให้อนุญาโตตุลาการต้องปฏิบัติหน้าที่อย่างเป็นอิสระและปราศจากอคติ (มาตรา 19) การที่อนุญาโตตุลาการเข้าไปช่วยทนายฝ่ายหนึ่งเตรียมการซักถามพยาน เช่น การแนะนำคำถามหรือกลยุทธ์เพื่อโจมตีพยานฝ่ายตรงข้าม ถือเป็นการละเมิดหลักการนี้อย่างชัดเจน การกระทำดังกล่าวไม่เพียงทำให้ฝ่ายที่เสียเปรียบรู้สึกถึงความอยุติธรรม แต่ยังบ่อนทำลายความเชื่อมั่นในกระบวนการทั้งหมด ซึ่งอาจส่งผลให้คู่กรณีปฏิเสธที่จะยอมรับคำชี้ขาดในท้ายที่สุด

2. ผลกระทบต่อคำชี้ขาดของอนุญาโตตุลาการ

ตามพระราชบัญญัติอนุญาโตตุลาการ พ.ศ. 2545 มาตรา 40 คู่กรณีมีสิทธิยื่นคำร้องต่อศาลขอให้เพิกถอนคำชี้ขาดของอนุญาโตตุลาการได้ หากพิสูจน์ได้ว่ากระบวนการไม่เป็นไปตามหลักยุติธรรม หรืออนุญาโตตุลาการมีความลำเอียง หากฝ่ายที่เสียเปรียบสามารถนำหลักฐานมาแสดงได้ว่าอนุญาโตตุลาการช่วยฝ่ายตรงข้ามซ้อมการซักถามพยาน เช่น บันทึกการสนทนา หรือพยานบุคคล ศาลอาจตัดสินให้คำชี้ขาดนั้นเป็นโมฆะ ส่งผลให้กระบวนการที่ใช้เวลานานและเสียค่าใช้จ่ายสูงต้องสูญเปล่า คู่กรณีอาจต้องเริ่มต้นกระบวนการใหม่หรือนำข้อพิพาทเข้าสู่ศาล ซึ่งขัดกับเจตนารมณ์ของการเลือกใช้ระบบอนุญาโตตุลาการตั้งแต่แรก

3. ผลกระทบทางจริยธรรมและชื่อเสียง

ในประเทศไทย อนุญาโตตุลาการมักเป็นผู้เชี่ยวชาญที่มีชื่อเสียง เช่น อดีตผู้พิพากษา ทนายความ หรือนักวิชาการ การกระทำที่ขาดความเป็นกลาง เช่น การช่วยฝ่ายหนึ่งเตรียมการซักถามพยาน ไม่เพียงแต่เป็นการละเมิดจรรยาบรรณของวิชาชีพ แต่ยังทำลายชื่อเสียงส่วนตัวและความน่าเชื่อถือของสถาบันอนุญาโตตุลาการที่ตนสังกัด เช่น สถาบันอนุญาโตตุลาการ (Thailand Arbitration Center – THAC) หากเรื่องนี้ถูกเปิดเผยสู่สาธารณะ อาจเกิดกระแสวิพากษ์วิจารณ์และลดทอนความเชื่อมั่นในระบบอนุญาโตตุลาการของไทยในสายตานักลงทุนทั้งในและต่างประเทศ

4. ผลกระทบในทางปฏิบัติต่อข้อพิพาท

การซ้อมซักถามพยานโดยมีอนุญาโตตุลาการช่วยเหลือ อาจทำให้ฝ่ายที่ได้รับการช่วยเหลือได้เปรียบอย่างไม่เป็นธรรม เช่น รู้จุดอ่อนของพยานฝ่ายตรงข้ามล่วงหน้า หรือสามารถกำหนดคำถามที่บิดเบือนข้อเท็จจริงได้อย่างแยบยล ส่งผลให้การนำเสนอพยานหลักฐานในชั้นอนุญาโตตุลาการเสียสมดุล คำชี้ขาดที่ออกมาอาจไม่สะท้อนความจริงทั้งหมด และนำไปสู่ผลลัพธ์ที่ไม่ยุติธรรมต่อฝ่ายที่เสียเปรียบ

5. ทางออกและการป้องกัน

เพื่อป้องกันปัญหานี้ ระบบอนุญาโตตุลาการไทยควรมีการกำกับดูแลที่เข้มงวดมากขึ้น เช่น การกำหนดแนวปฏิบัติที่ชัดเจนเกี่ยวกับการติดต่อระหว่างอนุญาโตตุลาการและคู่กรณี รวมถึงการจัดอบรมจริยธรรมอย่างสม่ำเสมอ นอกจากนี้ คู่กรณีควรมีสิทธิร้องขอให้เปลี่ยนตัวอนุญาโตตุลาการได้ทันที หากมีเหตุสงสัยเรื่องความเป็นกลางตั้งแต่ต้นกระบวนการ (ตามมาตรา 20 ของ พ.ร.บ. อนุญาโตตุลาการ พ.ศ. 2545)

สรุปส่งท้าย

เมื่ออนุญาโตตุลาการไทยไม่เป็นกลาง และเข้าไปช่วยทนายฝ่ายหนึ่งซ้อมการซักถามพยานเพื่อใช้ถามพยานอีกฝ่าย ผลที่ตามมาคือการสูญเสียความเป็นธรรม ความน่าเชื่อถือของคำชี้ขาด และอาจนำไปสู่การเพิกถอนคำตัดสินโดยศาล นอกจากนี้ยังส่งผลกระทบต่อชื่อเสียงของอนุญาโตตุลาการและระบบกฎหมายไทยในภาพรวม การรักษาความเป็นกลางจึงไม่ใช่เพียงหน้าที่ของอนุญาโตตุลาการเท่านั้น แต่ยังเป็นรากฐานสำคัญที่ทำให้ระบบอนุญาโตตุลาการยังคงเป็นทางเลือกที่ไว้วางใจได้ในการระงับข้อพิพาท

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง