The Linguistic Power Play: Authority, Fidelity, and Morale in Thai Arbitration Interpretation

In the intricate world of arbitration, where words serve as the foundation of justice, the role of interpreters is both indispensable and precarious. Interpreters bridge linguistic divides, ensuring that testimonies and arguments are accurately conveyed across cultures and legal systems. Yet, in Thai arbitration proceedings, this role is fraught with challenges that extend beyond mere translation. The interplay of authority, exercised through language by the “lawyer’s interpreter” and the “opposing Thai arbitrator,” often undermines the fidelity of interpretation and erodes the morale of interpreters. This article explores how such dynamics manifest, drawing from a specific case where a witness’s casual remark, “แล้วก็เซ็นต์ในสัญญา” (“and then signed the contract”), was transformed into the legally charged “as I see it is executed,” and how an opposing arbitrator’s finger-pointing inquiry—”Did you translate?”—exemplifies a broader cultural tension. Through a linguistic and cultural lens, we examine the ramifications of these practices and propose pathways toward a more equitable arbitration environment.

The Authority of Language in Arbitration

Language in legal settings is rarely neutral; it is a tool of power, wielded to shape perceptions and influence outcomes. In the scenario under scrutiny, two key figures—the “lawyer’s interpreter” and the “opposing Thai arbitrator”—employ language in ways that assert dominance over the interpretive process, often to the detriment of the interpreter’s autonomy and well-being.

The “lawyer’s interpreter” occupies a dual role: a linguistic conduit and, at times, an unwitting pawn in legal strategy. When a witness casually states “แล้วก็เซ็นต์ในสัญญา,” a phrase rooted in everyday Thai vernacular meaning to sign a document, the interpreter’s rendition as “as I see it is executed” introduces a significant shift. In English legal parlance, “executed” transcends mere signing; it implies a completed act with binding force—a nuance absent from the witness’s original intent. This transformation is not a mere linguistic slip but a deliberate reframing, likely driven by the instructing lawyer’s agenda to present the witness’s testimony as legally conclusive. Such manipulation highlights a troubling exercise of authority, where the interpreter’s fidelity to the source is sacrificed for strategic gain.

Conversely, the “opposing Thai arbitrator” exerts authority through direct confrontation. By pointing a finger and demanding, “Did you translate?” in a commanding tone, the arbitrator disrupts the interpreter’s workflow and asserts dominance. This behavior stands in stark contrast to international norms, where arbitrators address interpreters with courtesy—e.g., “Madam Interpreter, could you speak louder please?”—acknowledging their critical role. In Thailand, however, this interaction reflects a cultural tendency to prioritize hierarchy over collaboration, placing the interpreter in a subservient position and amplifying their vulnerability.

Fidelity Under Fire: The Ethics of Interpretation

At the heart of interpretation lies a fundamental ethical mandate: to preserve the speaker’s meaning with unwavering fidelity. The distortion of “เซ็นต์ในสัญญา” into “executed” breaches this principle. Linguistically, the Thai phrase is neutral and informal, devoid of the legal weight that “executed” imposes. This discrepancy matters profoundly in arbitration, where precise wording can sway a tribunal’s interpretation of intent and liability. By injecting a legalistic gloss, the lawyer’s interpreter not only misrepresents the witness but also undermines the integrity of the proceedings.

This infidelity is not solely the interpreter’s burden to bear. Pressure from lawyers, eager to mold testimony into a favorable narrative, often compels interpreters to stray from neutrality. In this case, the lawyer’s intent to render every utterance in legal terms—transforming casual speech into a form easily digestible by adjudicators—shifts the interpreter’s role from translator to co-strategist. Such dynamics violate the interpreter’s code of impartiality, creating an ethical quandary: adhere to professional standards or bend to the will of the hiring party?

The Toll on Morale: A Cultural Collision

The cumulative effect of these linguistic power plays is a profound erosion of the interpreter’s morale. For the interpreter, witnessing their craft distorted by a colleague—such as the lawyer’s interpreter—strikes at the core of professional pride. The internal conflict between duty and coercion breeds frustration, as theinterpreter grapples with a compromised rendition of truth. This is compounded by the opposing arbitrator’s aggression, which devalues the interpreter’s contribution and heightens workplace stress. The pointed finger and raised voice are not mere annoyances; they are symbolic assaults on dignity, signaling that the interpreter’s role is subordinate rather than essential.

This dynamic is deeply rooted in Thai cultural norms, where deference to authority often trumps mutual respect. Should the interpreter protest, they risk being branded disrespectful—a serious accusation in a hierarchical society. This cultural bind leaves interpreters trapped: endure silently or jeopardize their standing. In contrast, international arbitration settings prioritize professionalism and equity, treating interpreters as partners in the process. The Thai approach, by contrast, fosters an environment where morale suffers, and with it, the quality of interpretation.

Toward a Balanced Future: Recommendations

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach that bridges cultural practices with global standards:

- Upholding Interpretive Standards: Interpreters must be empowered to resist external pressures, adhering strictly to the principle of fidelity. Legal teams should bear the burden of arguing interpretive nuances, rather than expecting interpreters to reshape testimony. Clear guidelines, reinforced by professional bodies, can bolster this autonomy.

- Cultural Training for Arbitrators: Thai arbitrators would benefit from training in international etiquette, emphasizing respectful engagement with all participants, including interpreters. Replacing commands with requests—e.g., “Could you clarify the translation?”—can foster a collaborative atmosphere.

- Support Systems for Interpreters: Professional associations should offer interpreters psychological and legal support, providing a safe space to address grievances and assert their rights. This safety net can mitigate the toll of workplace pressures.

Conclusion

In Thai arbitration, the interplay of linguistic authority and cultural norms reveals a troubling imbalance. The “lawyer’s interpreter,” swayed by legal agendas, distorts casual speech into binding terms, while the “opposing Thai arbitrator” reinforces dominance through confrontational language. Together, these forces compromise fidelity and batter the interpreter’s morale, exposing a rift between Thai practices and international ideals. By realigning these dynamics—through ethical rigor, cultural sensitivity, and robust support—arbitration in Thailand can evolve into a space where interpreters thrive, not merely survive, ensuring that justice is not lost in translation.

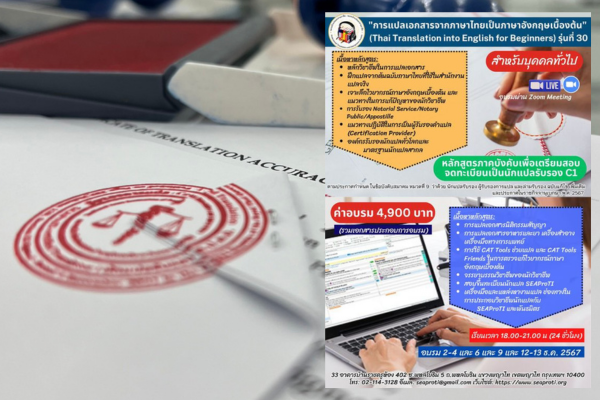

SEAProTI’s certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters:

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for individuals to register as “Certified Translators,” “Translation Certification Providers,” and “Certified Interpreters” under the association’s regulations. These guidelines are detailed in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet under the Office of the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, dated July 25, 2024, Volume 141, Part 66 Ng, Page 100.

To read the full publication, visit: the Royal Thai Government Gazette

การต่อสู้ด้วยภาษา: อำนาจ ความซื่อสัตย์ และขวัญกำลังใจในการแปลของอนุญาโตตุลาการไทย

22 กุมภาพันธ์ 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ในโลกอันซับซ้อนของกระบวนการอนุญาโตตุลาการ คำพูดคือรากฐานของความยุติธรรม ล่ามมีบทบาทสำคัญยิ่งในการเชื่อมโยงความแตกต่างทางภาษา เพื่อให้คำให้การและข้อโต้แย้งถูกถ่ายทอดอย่างแม่นยำข้ามวัฒนธรรมและระบบกฎหมาย อย่างไรก็ตาม ในบริบทของอนุญาโตตุลาการไทย บทบาทนี้เต็มไปด้วยความท้าทายที่ไม่ได้จำกัดอยู่แค่การแปลภาษา การปะทะกันของอำนาจที่แสดงออกผ่านภาษาโดย “ล่ามทนายความ” และ “อนุญาโตตุลาการไทยฝ่ายตรงข้าม” มักบั่นทอนความซื่อสัตย์ของการแปลและทำลายขวัญกำลังใจของล่าม บทความนี้สำรวจว่าปรากฏการณ์เหล่านี้เกิดขึ้นได้อย่างไร โดยอ้างอิงกรณีที่พยานพูดอย่างไม่เป็นทางการว่า “แล้วก็เซ็นต์ในสัญญา” แต่ถูกแปลเป็น “as I see it is executed” ที่มีความหมายทางกฎหมาย และการที่อนุญาโตตุลาการฝ่ายตรงข้ามชี้หน้าถามว่า “Did you translate?” ซึ่งสะท้อนถึงความตึงเครียดทางวัฒนธรรมที่กว้างขึ้น ผ่านมุมมองทางภาษาศาสตร์และวัฒนธรรม เราจะวิเคราะห์ผลกระทบของพฤติกรรมเหล่านี้และเสนอแนวทางสู่สภาพแวดล้อมอนุญาโตตุลาการที่เท่าเทียมมากขึ้น

อำนาจของภาษาในอนุญาโตตุลาการ

ภาษาในบริบทกฎหมายไม่เคยเป็นกลาง มันคือเครื่องมือของอำนาจที่ถูกใช้เพื่อกำหนดมุมมองและมีอิทธิพลต่อผลลัพธ์ ในกรณีที่เราศึกษา บุคคลสำคัญสองฝ่าย—“ล่ามทนายความ” และ “อนุญาโตตุลาการไทยฝ่ายตรงข้าม”—ใช้ภาษาในลักษณะที่แสดงอำนาจเหนือกระบวนการแปล ซึ่งมักส่งผลเสียต่ออิสระและสภาพจิตใจของล่าม

“ล่ามทนายความ” ต้องรับบทบาทคู่—ทั้งเป็นสื่อกลางทางภาษาและบางครั้งกลายเป็นเครื่องมือในกลยุทธ์กฎหมายโดยไม่รู้ตัว เมื่อพยานพูดว่า “แล้วก็เซ็นต์ในสัญญา” ซึ่งเป็นสำนวนในภาษาพูดไทยทั่วไปที่หมายถึงการลงลายมือชื่อในเอกสาร การแปลเป็น “as I see it is executed” ได้เปลี่ยนความหมายไปอย่างมาก ในภาษาอังกฤษคำว่า “executed” ไม่ได้หมายถึงแค่การเซ็นชื่อ แต่บ่งบอกถึงการกระทำที่สมบูรณ์และมีผลผูกพันตามกฎหมาย—ความหมายที่พยานไม่ได้ตั้งใจสื่อ การเปลี่ยนแปลงนี้ไม่ใช่ความผิดพลาดทางภาษาธรรมดา แต่เป็นการปรับแต่งโดยเจตนา ซึ่งน่าจะเกิดจากแรงกดดันของทนายความที่ต้องการให้คำให้การของพยานดูมีน้ำหนักทางกฎหมาย การกระทำนี้เผยให้เห็นการใช้อำนาจที่สร้างปัญหา โดยความซื่อสัตย์ต่อคำพูดต้นฉบับถูกเสียสละเพื่อผลประโยชน์เชิงกลยุทธ์

ในทางกลับกัน “อนุญาโตตุลาการไทยฝ่ายตรงข้าม” แสดงอำนาจผ่านการเผชิญหน้าโดยตรง การชี้หน้าล่ามพร้อมตะโกนถามว่า “Did you translate?” ขัดขวางการทำงานของล่ามและยืนยันความเหนือกว่า พฤติกรรมนี้แตกต่างอย่างสิ้นเชิงกับมาตรฐานสากล ที่อนุญาโตตุลาการมักปฏิบัติต่อล่ามด้วยความสุภาพ เช่น “คุณล่ามครับ/ค่ะ ขอให้พูดดังขึ้นได้ไหมครับ/คะ?” โดยยอมรับถึงบทบาทสำคัญของล่าม แต่ในประเทศไทย การโต้ตอบเช่นนี้สะท้อนถึงแนวโน้มทางวัฒนธรรมที่ให้ความสำคัญกับลำดับชั้นมากกว่าการทำงานร่วมกัน ทำให้ล่ามอยู่ในสถานะที่ด้อยกว่าและเปราะบาง

ความซื่อสัตย์ที่ถูกท้าทาย: จริยธรรมของการแปล

หัวใจของการแปลคือพันธะทางจริยธรรมที่ต้องรักษาความหมายและเจตนาของผู้พูดให้คงเดิมอย่างเคร่งครัด การบิดเบือน “เซ็นต์ในสัญญา” เป็น “executed” ละเมิดหลักการนี้ ในทางภาษาศาสตร์ วลีในภาษาไทยนี้เป็นคำพูดที่เป็นกลางและไม่เป็นทางการ ไม่มีน้ำหนักทางกฎหมายที่คำว่า “executed” นำมาให้ ความแตกต่างนี้สำคัญอย่างยิ่งในอนุญาโตตุลาการ ที่คำพูดที่แม่นยำสามารถมีผลต่อการตีความเจตนาและความรับผิดชอบของคู่กรณี การเติมความหมายทางกฎหมายเข้าไป ล่ามทนายความไม่เพียงบิดเบือนคำพูดของพยาน แต่ยังบ่อนทำลายความน่าเชื่อถือของกระบวนการ

ความไม่ซื่อสัตย์นี้ไม่ใช่ภาระที่ล่ามต้องแบกรับเพียงลำพัง แรงกดดันจากทนายความที่ต้องการปรับคำให้การให้เข้ากับเรื่องเล่าที่เป็นประโยชน์ต่อฝ่ายตน มักบีบให้ล่ามหลีกเลี่ยงความเป็นกลาง ในกรณีนี้ ความตั้งใจของทนายที่ต้องการให้ทุกคำพูดกลายเป็นภาษากฎหมาย—เปลี่ยนคำพูดทั่วไปให้เข้าใจง่ายสำหรับผู้ตัดสิน—ได้เปลี่ยนบทบาทของล่ามจากผู้แปลเป็นผู้ร่วมวางกลยุทธ์ พฤติกรรมนี้ขัดแย้งกับจรรยาบรรณของล่ามที่ต้องรักษาความเป็นธรรม สร้างภาวะกลืนไม่เข้าคายไม่ออก: จะยึดตามมาตรฐานวิชาชีพ หรือยอมจำนนต่อความต้องการของผู้ว่าจ้าง?

ผลกระทบต่อขวัญกำลังใจ: การปะทะทางวัฒนธรรม

ผลกระทบสะสมจากเกมอำนาจทางภาษาเหล่านี้คือการพังทลายของขวัญกำลังใจของล่ามอย่างรุนแรง สำหรับล่าม การเห็นงานของตนถูกบิดเบือนโดยเพื่อนร่วมงาน เช่น ล่ามทนายความ โจมตีความภาคภูมิใจในวิชาชีพ ความขัดแย้งภายในระหว่างหน้าที่และการถูกบังคับก่อให้เกิดความหงุดหงิด เมื่อล่ามต้องต่อสู้กับการถ่ายทอดความจริงที่ถูกบิดเบือน สถานการณ์นี้ยิ่งเลวร้ายลงด้วยความก้าวร้าวของอนุญาโตตุลาการฝ่ายตรงข้าม ซึ่งลดคุณค่าของล่ามและเพิ่มความเครียดในที่ทำงาน การชี้หน้าและน้ำเสียงดังไม่ใช่แค่เรื่องน่ารำคาญ แต่เป็นการโจมตีศักดิ์ศรีเชิงสัญลักษณ์ บ่งบอกว่าบทบาทของล่ามเป็นเพียงผู้ใต้บังคับบัญชา ไม่ใช่ส่วนสำคัญ

ปรากฏการณ์นี้หยั่งรากลึกในวัฒนธรรมไทย ที่การยอมรับอำนาจมักมาก่อนความเคารพซึ่งกันและกัน หากล่ามแสดงความไม่พอใจ พวกเขาอาจถูกตราหน้าว่าไม่เคารพ—whichถือเป็นข้อกล่าวหาที่ร้ายแรงในสังคมที่มีลำดับชั้น ความขัดแย้งทางวัฒนธรรมนี้ทำให้ล่ามติดอยู่ในสถานการณ์ที่ยากลำบาก: อดทนเงียบ ๆ หรือเสี่ยงต่อการเสียตำแหน่ง ในทางตรงกันข้าม กระบวนการอนุญาโตตุลาการสากลให้ความสำคัญกับความเป็นมืออาชีพและความเท่าเทียม ปฏิบัติต่อล่ามในฐานะพันธมิตรในกระบวนการ แนวทางของไทยกลับสร้างสภาพแวดล้อมที่ขวัญกำลังใจถูกทำลาย และส่งผลต่อคุณภาพของการแปล

สู่ความสมดุลในอนาคต: ข้อเสนอแนะ

การแก้ไขความท้าทายเหล่านี้ต้องใช้แนวทางหลายมิติที่เชื่อมโยงวัฒนธรรมท้องถิ่นกับมาตรฐานสากล:

- รักษามาตรฐานการแปล: ล่ามต้องได้รับอำนาจในการต้านทานแรงกดดันจากภายนอก โดยยึดมั่นในหลักการความซื่อสัตย์อย่างเคร่งครัด ทีมกฎหมายควรรับผิดชอบในการโต้แย้งความหมาย ไม่ใช่คาดหวังให้ล่ามปรับคำให้การ แนวทางที่ชัดเจนจากองค์กรวิชาชีพสามารถเสริมสร้างอิสระนี้ได้

- อบรมวัฒนธรรมสำหรับอนุญาโตตุลาการ: อนุญาโตตุลาการไทยควรได้รับการฝึกอบรมด้านมารยาทสากล โดยเน้นการมีส่วนร่วมอย่างเคารพกับทุกฝ่าย รวมถึงล่าม การเปลี่ยนคำสั่งเป็นคำขอ เช่น “ช่วยชี้แจงการแปลหน่อยได้ไหมครับ/คะ?” สามารถสร้างบรรยากาศการทำงานร่วมกันได้

- ระบบสนับสนุนล่าม: สมาคมวิชาชีพควรให้การสนับสนุนด้านจิตใจและกฎหมายแก่ล่าม มอบพื้นที่ปลอดภัยในการระบายปัญหาและปกป้องสิทธิของตน เครือข่ายนี้สามารถลดผลกระทบจากความกดดันในที่ทำงานได้

บทสรุป

ในอนุญาโตตุลาการไทย การปะทะกันของอำนาจทางภาษาและบรรทัดฐานวัฒนธรรมเผยให้เห็นความไม่สมดุลที่น่ากังวล “ล่ามทนายความ” ที่ถูกชักจูงโดยเป้าหมายทางกฎหมาย บิดเบือนคำพูดทั่วไปให้กลายเป็นคำที่มีผลผูกพัน ขณะที่ “อนุญาโตตุลาการไทยฝ่ายตรงข้าม” ตอกย้ำอำนาจด้วยภาษาที่เผชิญหน้า ทั้งสองร่วมกันทำลายความซื่อสัตย์และบั่นทอนขวัญกำลังใจของล่าม แสดงถึงช่องว่างระหว่างแนวปฏิบัติของไทยและอุดมคติสากล การปรับปรุงสถานการณ์นี้—ผ่านความเข้มงวดทางจริยธรรม ความอ่อนไหวต่อวัฒนธรรม และการสนับสนุนที่แข็งแกร่ง—สามารถเปลี่ยนอนุญาโตตุลาการในประเทศไทยให้เป็นพื้นที่ที่ล่ามเติบโตได้ ไม่ใช่แค่รอดชีวิต เพื่อให้ความยุติธรรมไม่สูญหายไปในการแปล

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง